Starting today and slated to appear in this space every Tuesday and Friday in the weeks and months ahead is a new Faith and Fear in Flushing series: A Met for All Seasons. In it, Jason and I will consider a given Met who played in a given season and…well, we’ll see.

Here’s the background: We conducted a draft nine years ago when a semblance of this concept first occurred to us; one of us would do this player for this year; the other of us would do that player for that year; and so on. The “so on” became nothing except for an occasional “hey, remember that thing we were gonna do?” Luckily, we’d each saved our draft lists. Thus, a little while ago, once we realized we weren’t going to be busy recapping games for the foreseeable future, we extended the draft eligibility period, held some supplemental rounds, implemented a compensation pool (allowing us to replace any selections we’d rethought since 2011, given that it worked so well for the White Sox in 1984) and certified our choices.

Now, after nearly a decade of talking and not talking about it, we each have thirty players bearing the banner for a particular year and will set out to explain, to some extent, why we chose who we chose and what they mean to us as Mets fans. Some weeks I’ll go Tuesday and Jason will go Friday; some weeks it will work the other way around. (Coincidentally, Jason and I once went in on a Tuesday/Friday ticket plan.) The seasons we’re covering are 1962 through 2021, the last couple encompassing an air of mystery or perhaps optimism. The Mets we’re talking about will be revealed in due time. We’d like to think they represent a decent cross-section of the Met experience over the nearly sixty years there’ve been Mets, but maybe we just picked players we wanted to write about. The order in which they’ll appear is non-chronological.

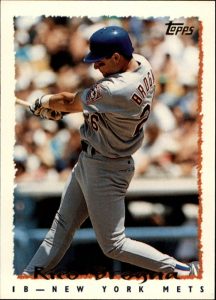

For example, I’m starting with 1994 and my Met for that season is Rico Brogna.

Rico Brogna is my Met for 1994 as a person, I suppose, but probably more as an idea. I think I’m going to find out as we do this that I tend to think of ballplayers as ideas as much as I do people. I have it on good authority — hell, I’ve witnessed it for myself — that ballplayers are people, too. We probably forget that from time to time, considering we only know of these people because they are ballplayers. That’s generally good enough for us, the fans.

We’re people as well, but we’re talking baseball here.

I immediately think of Rico Brogna when I think of the 1994 Mets season because of the idea he represented to me coming out of that strike-shortened year. Rico Brogna was who and what I wanted to come back. He’d brought me hope and I figured he could only deliver more. I was going to hold tight during absent August, silent September, ohfer October, the long, even colder winter, and the farce spring when MLB lured replacement players to wear their clubs’ uniforms in games that didn’t count, threatening to keep them around for games that did. By April 26, 1995, the latest the Mets have ever opened a season (until 2020, if they open one at all), I should have been fed up with baseball, which didn’t even have the dignity to be around for months on end to let me be fed up with it.

Instead, I kept hanging tight, waiting for Rico and welcomed back the whole package, lock, stock and Brogna. Twenty-five years later, deep in a void that superficially recalls the lack of baseball wrought by the 1994-1995 strike, I can’t say it was Rico Brogna the person or even Rico Brogna the player I wanted. I wanted Rico Brogna the idea.

Rico Brogna debuted as a Met on June 22, 1994. I had never heard of him despite his having been a first-round draft pick of the Detroit Tigers in 1988. He came up to majors four years later, played nine games, and returned to Triple-A Toledo for another year. I missed it when the Mets traded their own former first-rounder, Alan Zinter (1989), for Brogna four days before Opening Day 1994. The Mets were busy that week. They picked up David Segui on March 27, Jose Vizcaino on March 30. So overcome with joy that the 1994 Mets would be even more materially different from the nightmare 1993 Mets, I guess I didn’t squint all the way to bottom of the transactions box for March 31 to see this extra move.

With Vizcaino at short, Segui at first and Brogna assigned to Norfolk, the post-apocalyptic Mets got off to a modestly brilliant start in 1994. Anything that wasn’t indicative of another 59-103 record would have struck me as modestly brilliant. The Mets swept their first three in Chicago, returned to Shea for their Home Opener with a winning record and levitated themselves four games over .500 after 32 games. In New York in May 1994, with all five winter sports teams having made the playoffs — and the Knicks, Rangers and Devils all legitimately carrying championship aspirations — it felt like nobody outside the hardest core of Mets fans was paying attention. But I was, and I was delighted that the Mets were, after a three-year dip in fortunes, kind of OK again.

The high times of 18-14 didn’t last, but I was slow to get the memo. I didn’t want to read it. I was convinced the Mets were pretty good. Alas, the dark side of .500 beckoned for keeps in early June. Fifth place in the newly aligned National League East, which is to say the basement, loomed as our summer home. I didn’t maintain any allusion we could keep up with the Expos or Braves or anybody else vying for the new Wild Card, but I just liked that the 1994 Mets weren’t the 1993 Mets anymore. I wanted them to quit reminding me a year hadn’t passed since they were the 1993 Mets.

The Rangers won the Stanley Cup on June 14. The Knicks took the Rockets to the seventh game of the NBA Finals on June 22. In between, David Segui went on the 15-day disabled list, necessitating the promotion from Norfolk of Rico Brogna. I know which one of those sports stories resonates most for me now, but like I said, I didn’t know anything about Rico Brogna then. I was only getting used to him replacing Segui on June 28 when word came down that Dwight Gooden — who’d pitched Opening Day in Chicago and still reigned at least titularly as ace of the Mets’ rotation — tested positive for cocaine and was about to be suspended, just as happened in 1987. Doc, my favorite player ever since he first emerged as breathtaking Dr. K, went through rehab seven years before and was welcomed back as if not a hero, then definitely as family. In 1994, he was essentially kicked out of the house. There was little in the way of acknowledging addiction as a disease, just disbelief that this was happening a second time, how could anybody with so much to lose be addled enough to lose it? Yup, the Mets were finally getting headlines.

On the night the news of Doc’s KO broke, Rico Brogna started his third consecutive game for the Mets and, for the third consecutive game, recorded a pair of hits, including his first National League home run. The Mets lost, falling ten below .500 for the first time in 1994, but Rico raised his average to .333.

Without meaning to, Rico Brogna filled the opening for my favorite player before I had time to place a classified. Doc wasn’t around. Rico was. I learned about him. He was 24, born in Massachusetts, but grew up to become the pride of Watertown, Conn., from whence he was drafted. Played high school football well, we heard. Became buddies with the pitcher called up to take Doc’s spot in the rotation, Jason Jacome (pronounced hock-a-me). They were spotted palling around on a West Coast trip, the two new guys grabbing tenuous hold of the steering wheel for a franchise that had once more lost its way. In 1984, it was Gooden joining forces with Strawberry. In April it was Segui and Vizcaino. Now it was these two newest newcomers, 24-year-old Rico, 23-year-old Jason, a couple of lefties from out of nowhere. On July 7, in his second start, Jacome shut out the Dodgers, lifting the Mets to their sixth win in eight games since the night Doc was disappeared. Segui was back from the DL, but was planted for the time being in left field. A good glove man through his career, David was nonetheless Wally Pipped.

It would take a little while for Rico Brogna to settle in as a new age Lou Gehrig. There was a bit of slumping in California, but the Mets came home and the bat reheated. Rico’s average rose over .300 to stay. The Shea PA played “Rico Suave” when he’d get a big hit, briefly leading me to believe Brogna was Latino. I wasn’t corrected in this conception until some guy behind me at a game told his companion, “Brogna — that’s the Italian kid.” I didn’t care what Rico Brogna was other than that he was the Mets’ first baseman.

On July 25, a Monday night (I don’t have to look up the date or day), Rico Brogna exploded fully upon the Metropolitan-American consciousness, certainly the slice that was attempting to tune into The Baseball Network. The Baseball Network is hard to explain all these years later. It was hard to explain in 1994. Eschewing the “Game of the Week” motif as hopelessly outdated, MLB decided to have what amounted to a series of nationalized regional telecasts, with in-market exclusivity for particular games, which meant on a given weeknight, maybe you saw your favorite team, maybe you didn’t, no matter that they were all scheduled to play, no matter that cable networks existed in summertime to show baseball games. Sometimes New York got the Mets, sometimes it got that other New York team. And if the first-place Yankees ridiculously took TV precedence, the Mets were confined to radio. Got all that? Also, though these games aired on ABC, they were not announced by, say, Al Michaels. You got an announcer from one team and an announcer from another team and that was your crew. Actually, that was a pretty decent feature. Suddenly Bob Murphy was sometimes doing TV. On July 25, with the Mets in St. Louis and somehow rating preferential treatment back home on Channel 7, it was Gary Thorne, at this point part of the WWOR-TV booth, and Al Hrabosky.

They wound up co-hosting, live from Busch Stadium, The Rico Brogna Show. With as much spotlight as the 1994 Mets were going to garner, the young man from Connecticut raised his and therefore our profile. Brogna sizzled in St. Loo, going 5-for-5, making him the first Met to register five hits in one game in six years. His biggest hit was a two-run double that keyed a five-run fifth, giving Bret Saberhagen all the support he needed to cruise to a complete-game 7-1 win. Rico came into the game batting .333. He came out of it batting .377.

“I guess he’s what you would call a manager’s delight,” Saberhagen marveled. “It’s probably a night that I’ll remember for quite a while,” Bret’s first baseman allowed, humbly adding, “Some of the balls found some holes.”

Yes, sir, the 1994 Mets were rising like the mighty Mississippi. At least to me they were. They escaped the cellar. Saberhagen had made the All-Star team by walking basically nobody. Second baseman Jeff Kent showed he could hit a ton if not field quite as much. Vizcaino was a genuinely reliable all-around shortstop. Jason Jacome was en route to a winning record and the Mets began flirting seriously with one of their own. And Rico Brogna? He had, in my mind in about a month, ascended total obscurity to next big thing to biggest thing there could be, albeit on a limited scale.

Two-and-a-half weeks later, it all stopped, because the owners wanted to institute a salary cap and the players wanted no such thing and no compromise was forthcoming. On August 11, all the baseball on all the channels went dark and stayed dark. The blackout remained in effect clear through what was supposed to be the postseason, an affair that wasn’t remotely likely to include the 55-58 Mets, but I wasn’t aiming my sights that high one year after 1993. The previous August, former Cy Young winner Saberhagen was known mostly for blasting bleach at reporters, and former stolen base champ Vince Coleman was living down his contretemps that involved tossing powerful firecrackers at fans in the Dodger Stadium parking lot. Bobby Bonilla had been making threats, Eddie Murray snarled his hellos and everybody was stuck in a seventh-place snit. It was enough in August of 1994 that the fresher-faced third-place Mets were closing in on .500. It would have been great had they been granted the opportunity to reach it and hover above it.

After 113 games, almost .500 would have to do. I had that to cling to — that and seven home runs, twenty runs batted in and a .351 batting average I hadn’t anticipated in the slightest out of that fine young man from Watertown in his first 39 games as a Met. I had an idea of what Rico Brogna could do. I had an idea that Rico Brogna would keep making the Mets better. It would have to tide me over until whenever there’d again be baseball.

And it did.